Home >> Diversity and classification >> True fungi >> Dikarya >> Basidiomycota >> Agaricomycotina >> Jelly fungi

JELLY FUNGI

The term "jelly fungi" is an informal one applied to species of fungi having a gelatin-like consistency. The reason for this texture is that the structural hyphae of these fungi have walls that are not thin and rigid as they are in most fungi but instead are expanded out to a rather diffuse and indefinite extent. During dry periods these hyphae collapse down and become rather hard and resistant to bending, but as soon as they are moistened they expand back out to their original gelatinous texture. Such tissues are able to exist in a dry state for many months and, when exposed to moisture, quickly expand to full size. Therefore, fungi having these characteristics are suited to environments that may remain dry for long periods of time. They may be among the earliest fungi to be seen in the spring because they have remained dry and inconspicuous all winter, only to revive with the first melting snow or during winter thaws.

The peculiar texture of jelly fungi is not an absolute indicator of ancestral relationships. Gelatinous textures can also be found in some Ascomycota as well and are really just an adaptation to certain environmental pressures. Nevertheless some groups of fungi are almost entirely made up of species with gelatinous tissues while others are never gelatinous. Three groups stand out; the AURICULARIALES, the DACRYMYCETALES and the TREMELLALES. All of these have almost exclusively gelatinous basidiomata and all have basidia that are not conventional holobasidia. You may wish to review the discussion of basidium types before going further. A few more gelatinous species can be found among the Pucciniomycotina, but these are mostly small and inconspicuous.

AURICULARIALES

Auricularia auricula-judae, the Judas' ear fungus, is an umistakable species found on decaying wood of both hardwoods and conifers. In our region it is most commonly found on balsam fir, but in other areas it may be restricted to deciduous trees, especially elder. It was named after Judas Iscariot, who is believed to have hanged himself on an elder tree. This species occurs throughout the world and has become an important item in Asian cuisine. Bags of the dried basidiomata are sold in Chinese grocery stores under the name "wood ear". These are soaked in water to revive them and then added to a variety of dishes where they add a slightly crunchy texture. Another species, A. polytricha, sold under the name "cloud ear", is used in the same way. There are several species known; many are common in tropical forests. Species of Auricularia are unusual among the Agaricomycotina in having phragmobasidia.

Species of Exidia and Exidiopsis are found on dead branches of trees, both conifer and hardwood. They differ mainly by the form of their basidiomata: those of Exidia are mostly gelatinous and rounded to brain-like while those of Exidiopsis form flat resupinate growths. Exidia glandulosa, pictured at left, is typical of its genus in its black, spreading, gelatinous, brain-like masses of basidiomata. These particular basidiomata are sharing a dead aspen branch with the red basidiomata of Peniophora rufa, a quite unrelated fungus grouped among the corticioid and stereoid members of the diverse order Russulales. One point of caution here: not all species of Exidia have black basidiomata. Some are quite pale and could be mistaken for species of Tremella.

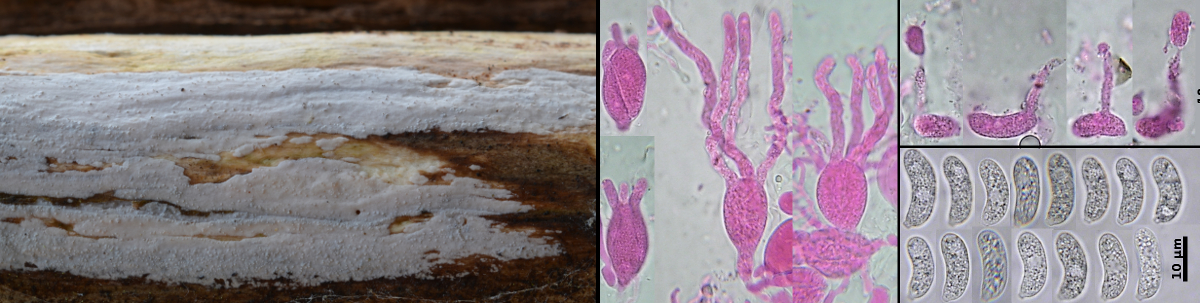

In the picure above, the flat white growth, on a dead branch of mountain ash, is Exidiopsis effusus. The panels at the lower right part of the illustration are microphotos of basidia and basidiospores of Exidiopsis effusus. The basidia are ellipsoidal and have remarkably long sterigmata. The basidiospores, made from a fresh spore print and mounted in water, have an allantoid (sausage) shape. These spores germinate by repetition, giving rise to a single sterigma bearing a small ballsitospore (a forcibly discharged spore), seen in the panel above the basidiospores. For these pictures the basidia and basidiospores were mounted in a KOH solution of Phloxine, a common stain used for basidiomycetes.

Two other fungi, illustrated above, deserve mention. These are, at left, Pseudohydnum gelatinosum and, at right, Tremiscus helvelloides. Pseudohydnum gelatinosum is common on conifer logs in the autumn and persists well into winter. It is unusual in having its cruciate basidia lining the surface of teeth in the manner of the tooth fungi. Tremiscus helvelloides also occurs on wood, but often on buried branches so that it appears to arise from the soil.

DACRYMYCETALES

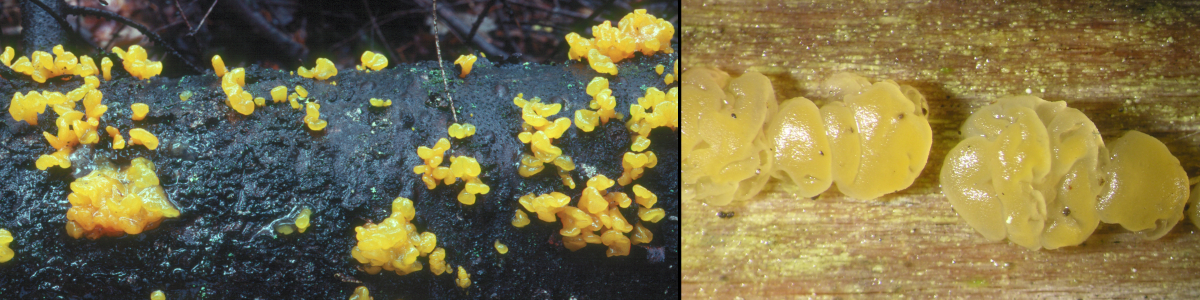

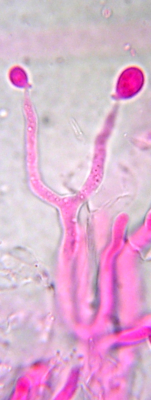

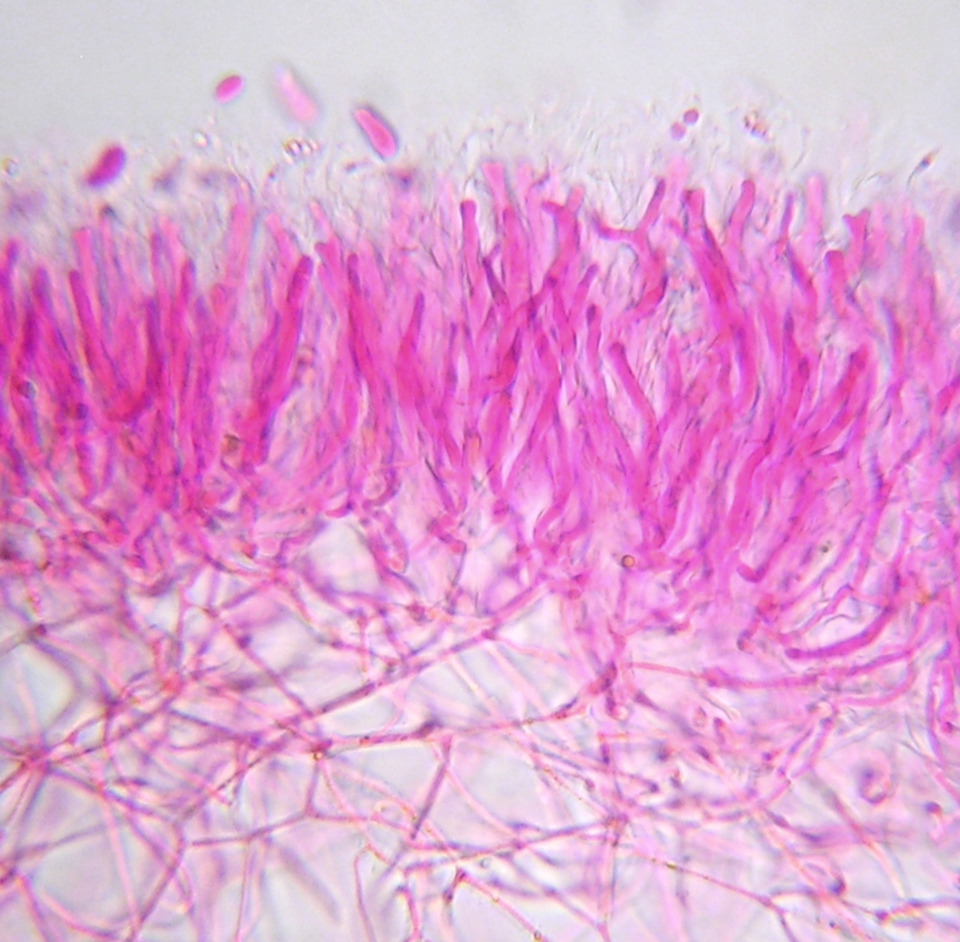

The Dacrymycetales, members of the class Dacrymycetes, are nearly all bright yellow to orange saprotrophs on wood, like Dacrymyces chrysospermus above left. All have tuning fork basidia as seen in the photo at far left. The basidiospores are unusual among Basidiomycota in that they may become septate at maturity. The picture, middle left, shows the stages in septum development in a species having basidiospores with an exceptional 15 septa at maturity. Because of their bright colour and massed fruiting bodies they are among the first fungi seen each spring. However, the highly conspicuous species D. chrysospermus may be misleading, many species are minute and only seen with a very good hand lens or dissecting microscope. For example, the basidiomata of Dacrymyces minor, seen in the highly magnified photo above right, are no more than 2 mm in diameter, and that is after being rehydrated. These were not seen in the field but were brought in with some other fungi and became apparent only after the wood had been soaked in water for an hour. As seen in the photo at near left, the hymenium of basidia and supporting structures rests upon a very loose gelatinous tissue. When these fungi are dry they shrink down to an inconspicuous mass or thin film, which explains why they are best sought during wet weather.

The species of Dacrymyces can be difficult to identify. A good microscope is necessary and even then the differences among species my be based on subtle differences in spore size, shape and germination characteristics. Species of Dacrymyces are sometimes referred to as "witches' butter", although this term is probably most properly applied to the unrelated Tremella mesenterica.

There are several other genera in the Dacrymycetales in addition to Dacrymyces. At right are two of these, Ditiola and Heterotextus. Ditiola radicata, at near right, is characterized by its white stipe. The specimen in the photograph was found on a bleached log on the shore of Mistinikon Lake in northern Ontario. Heterotextus alpinus, at far right, in common with species of Dacrymyces does not have a stipe but is characterized by conical basidiomata that are connected to the substrate at the tip of the cone. The basidia are produced on the wide flat surface.

TREMELLALES

The Tremellales, members of the Tremellomycetes, are mostly parasites on other fungi. They are found in a variety of habitats, almost always in the company of their fungal hosts. Tremella fuciformis, in the photo at left, is a fairly large member of its genus. It generally occurs in warmer parts of the world where it is a parasite on fungi that decay wood. The specimen in the photograph was collected in Florida. This species can easily be obtained by visiting a Chinese grocery store. It is commonly used in Asia as a dessert and is often served in a light sugar syrup. At one memorable meeting of mycologists in Toronto there was a banquet at a large Chinese restauant featuring different types of fungi. Dessert included T. fuciformis (called "snow fungus") served in the traditional way. Dr. Greg Thorn, one of the participants, was particularly sharp-eyed and noticed that the Tremella had tiny black spots on it and pulled out his hand lens for a closer look. He discovered that the Tremella, itself a fungal parasite, was being parasitized by perithecia of Ophiostoma epigloeum, a member of the Sordariomycetidae in the Ascomycota. This discovery became a matter of great interest and excitement to all the mycologists in the room and a concern to the restaurant management who had to be assured that the customers were delighted. In subsequent days Dr. Thorn investigated packets of T. fuciformis in several Chinese stores and found it to be common.

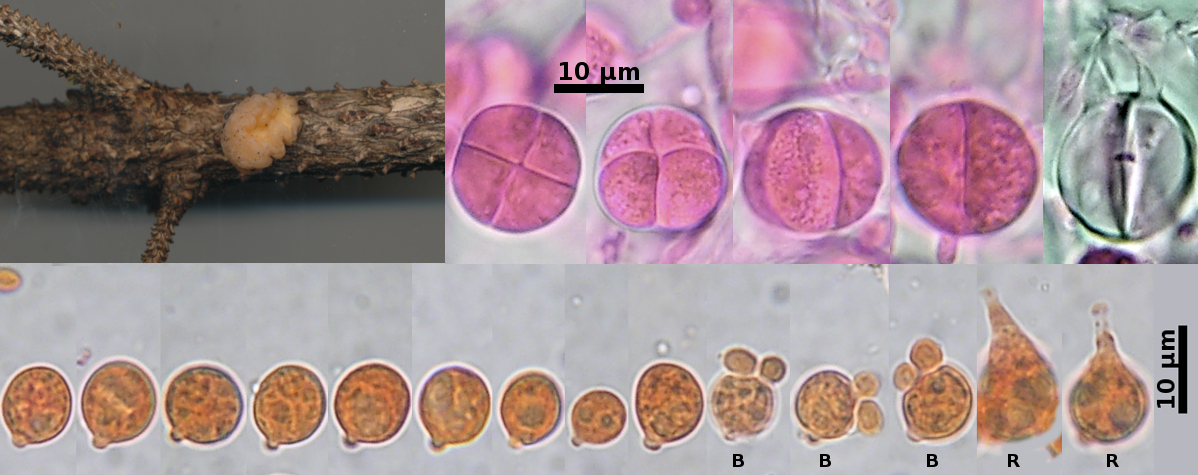

Tremella encephala, pictured above, usually produces smaller basidiomata than those of T. fuciformis, appearing as yellow brain-like or pustular masses on dead branches of coniferous trees. The one pictured here was collected on a small branch of red spruce in northern New Brunswick. It was parasitic on the hyphae of Stereum sanguinolentum, a basidiomycete producing conspicuous basidiomata on conifers. The basidiomata of S. sanginolentum are not visible in the photo because host and parasite were growing beneath the bark of the tree.

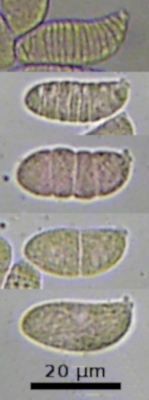

To the right of the macrophoto are several basidia of T. encephala, stained a pink colour in Phloxine and photographed in 5% KOH. Typical of all Tremellales these have cruciate septation. The basidia in the picture show a progression of views from vertical to lateral. The vertical view shows the characteristic cross-shaped or cruciate positioning of the septa. The basidium at far right shows two of the four horn-like sterigmata that function in the dispersal of the basidiospores. The basidiospores, stained in Congo Red. The first nine of these spores are ungerminated, while the rightmost five show two forms of germination. Those marked with a "B" have germinated by budding, a characteristic of fungi growing as yeasts. The ones marked with an "R" (for "repetitive germination") have produced sterigmata from which a ballistospore would be produced and forcibly discharged. "Ballistospore" is a term often applied to spores that are forcibly discharged from from a sterigma-like extension. It can also be applied to basidiospores, although this is not usually done.

Tremella mycophaga, a much smaller species is shown in the photo above. It forms small colourless basidiomata within the surface of the basidiomata of Aleurodiscus amorphus, a member of the corticioid Agaricomycetes discussed in some detail on these pages. Several of the orange basidiomata of A. amorphus growing along the top of the fir branch in the picture bear the white basidiomata of T. mycophaga. This small parasite is common wherever the host fungus occurs. There are many other small species of Tremella occurring on other fungi. They are difficult to collect because they are usually not apparent in the field and only show up when specimens of other fungi are being studied. Look for them on rainy days when they are swollen to their full size.