Home >> Diversity and classification >> True fungi >> Dikarya >> Basidiomycota >> Agaricomycotina >> Non-gilled macrofungi >> Corticioid and stereoid fungi

CORTICIOID AND STEREOID FUNGI

Corticioid and stereoid fungi bear their basidia and basidiospores over a surface that is smooth or nearly so. By definition they never have pores, teeth, lamellae or other basidium-bearing structures although, as always, there are gray areas where you have to make a decision about whether the surface is smooth or not. Corticioid fungi, such as Phlebiella sulphurea, above left, are resupinate, that is they lie flat on their sustrate, usually hanging upside-down on a horizontal surface such as the branch of a tree or seated on a vertical surface so that, either way, the basidiospores are able to fall into the air. Stereoid fungi are not resupinate and do not lie entirely flat on the substrate. Instead, as in Stereum sanguinolentum, above middle, they can become reflexed, meaning that they curve away from the substrate to form small brackets. Such reflexed stereoid fungi are often quite resupinate on the bottom of a surface such as a branch and become reflexed on the side of the branch, thus always allowing their spores a vertical fall. Some stereoid fungi, such as Thelephora terrestris at right grow on the ground and become rather mushroom-like, again offering their spores a vertical drop. In the picture, the basidioma at left was pulled out of the ground and turned over to show the hymenium (spore-bearing surface).

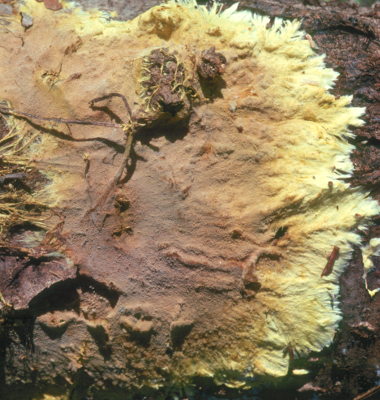

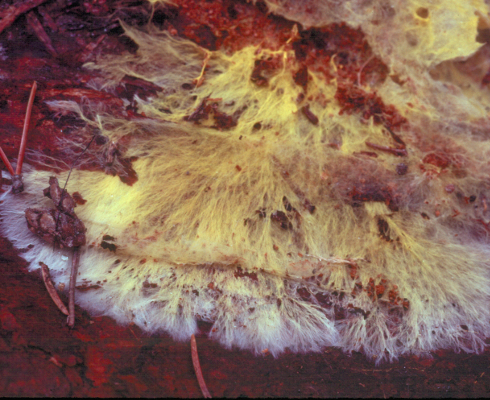

Although a few species of corticioid and stereoid fungi may cause plant disease most are either mycorrhizal or saprotrophs. The mycorrhizal ones, particularly the corticioid species, are still poorly studied compared to mycorrhizal mushrooms and other larger fungi. Most collectors generally assume that a corticioid fungus must be a saprotroph, although that is often not true. The fungus above left is Piloderma fallax a common mycorrhizal fungus associating with the roots of conifers. It is easily recognized by its bright yellow basidiomata found under rotting logs, often not growing directly on the wood. It is easy to trace its yellow hyphae away from the main part of the colony down to a root. In the picture above right a root of white spruce has been removed from the soil and cleaned to show the hyphae of P. fallax wrapped around each of the active root tips. Much experimental work has been done with this fungus so we know for certain that it forms mycorrhizae.

Confirming the mycorrhizal status of other species is difficult. One clue that the organism may be mycorrhizal is in its relationship to the substrate. Saprotrophic species usually grow directly on the substrate they are utilizing and seldom stray far from it. For example, they may be quite specific about the kind of wood they will decay and will be restricted to hardwoods or conifers or even to a single species. On the other hand, mycorrhiza-formers may fruit on any surface that is at hand, since the roots they are growing on are underground and not appropriate for the discharge of basidiospores into the air. Because of this mycorrhizal corticioid fungi like P. fallax are often found randomly attached to wood, leaves, sticks and even rocks. Byssocorticium atrovirens, figured at left, is probably another mycorrhizal species. Its strikingly blue-green basidiomata will be produced over any surface available. The one in the picture was collected on soil above the entrance to a small rodent burrow.

Thelephora terrestris, shown at the top right of this page, is a well-studied mycorrhizal fungus belonging to the order Thelephorales. Members of the Thelephorales are all mycorrhizal and have very distinctive microscopic features that make them easily recognized. However, their basidiomata take on a great variety of forms and are not just stereoid like species Thelephora. For example, the large genus Tomentella has entirely corticioid basidiomata that fruit on any available substrate.

The picture above offers three views of Aleurodiscus amorphus a saprotrophic corticioid member of the Russulales. It is a very common fungus in our area found on the underside of dead balsam fir branches. It nearly always grows on branches still attached to the tree and is thus exposed to extremes of heat and cold, wet and dry. Anything growing is such a habitat must be able to withstand extreme desiccation year around and be able to discharge its basidiospores when moisture is available. The particular fruiting bodies shown in the picture were collected in Charlotte County, New Brunswick in February 2006. They had been completely dry and frozen for much of the winter but on the day they were photographed there had been a thaw and light rain. The basidiomata were brought indoors and soaked in water for about an hour. One basidioma was kept suspended over a microscope slide for a few hours to see if it would discharge basidiospores. The picture at left shows the basidiomata as they appeared on the branch in the field. The centre picture shows the basidioma that had been suspended over the microscope slide and the strong deposit of orange basidiospores that had come from it. At right are several of the extra-large spiny basidiospores characteristic of this species. Read the essay on Real and Counterfeit Cup Fungi for more information about this interesting species.

The order Hymenochaetales is another group of fungi having a number of different basidioma types. The genus Hymenochaete represents this order within the corticioid/stereoid group. In the picture above H. tabacina is seen at left growing on a dead alder trunk and in the rest of the picture as "wings" on a very thin branch, also alder. The picture second from left shows the upper side of the stereoid basidioma of this species. The twig running the length of this picture is hard to distinguish. In the picture second from right the view is from the bottom and shows the hymenial (basidium-bearing) layer. Here the alder twig is a little more discernable. At far right is a higher magnification of the hymenium showing the sharp red setae produced by most Hymenochaetales. See the section on pore fungi for a closer look at these setae.

Two species commonly colonizing dead wood of poplar trees are shown above. At left is Peniophora rufa a member of the Russulales that is commonly found on dead aspen branches. The cushion-like basidiomata are bright red and very hard when they are dry. At right is Punctularia strigoso-zonata, a species found on poplar wood as well. Like P. rufa and Aleurodiscus amorphus it produces its basidiomata on branches well above the snow line and is thus exposed to dryness and cold. All of these species can be found in winter but will not display basidia and basidiospores until they have been soaked in water for a few hours and then kept moist for a few hours more until the current crop of basidia matures. These species are well adapted to wetting and drying. In one experiment a basidioma of P. strigoso-zonata was wetted, allowed to discharge its basidiospores and then dried again. This cycle was repeated 13 times before basidiospore production ceased.

The picture at left shows Leucogyrophana lichenicola, a corticioid member of the Boletales. Its yellow basidiomata are always found growing at the base of species of carpet lichens such as species of Cladonia and Cladina. It appears to be common in northern latitudes.

Some stereoid fungi produce their basidiomata as miniature cups and goblets. Although these add little structures seem different from the others discussed on this page they are really the same sort of thing. The picture at right is of a species of Maireina, one of the so-called "cyphelloid fungi", often seen on decaying branches of trees. Those growing above the snowline in winter have the same ability to revive and produce spores as those discussed above. Winter can be a productive time for the mycologist!