Home >> Diversity and classification >> True fungi >> Glomeromycota

GLOMEROMYCOTA

The Glomeromycota are not as diverse as other phyla of fungi nor are there as many species. However they make up for this uniformity by being among the most abundant and widespread of all fungi. As far as we know, all species of Glomeromycota are mutualistic with plants, forming arbuscular mycorrhizae.

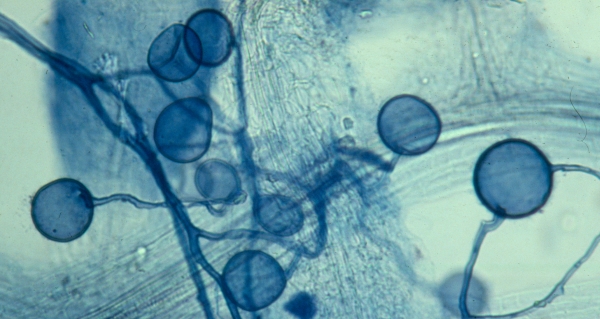

These fungi were considered to be members of the Zygomycota for many years, mainly because their hyphae lack septa and because their spores may superficially resemble zygospores. More recent genetic evidence shows that they are quite distinct from other fungi and definitely belong in a separate phylum. Palaeontologists have suspected this for a long time. The fossil roots of plants known to be as old as 450 million years clearly contain the hyphae and spores of Glomeromycota, showing this group to be among the oldest of fungi. The photograph above shows hyphae and spores of a species of Glomus, collected from the soil surrounding the roots of a balsam poplar tree. Such structures are indistinguishable from some fossil collections.

No member of the Glomeromycota has ever been grown in the laboratory independently of its plant associate. It is still not known exactly what these fungi need as nutrients. This inability to grow them is not because scientists have not tried very hard to do so. The Glomeromycota are of such fundamental importance to plant development that anyone who succeeded in growing them commercially would reap significant financial rewards.

The development of the Glomeromycota within a plant root has been studied extensively and nearly all produce structures called "arbuscules" within the cells of the roots.

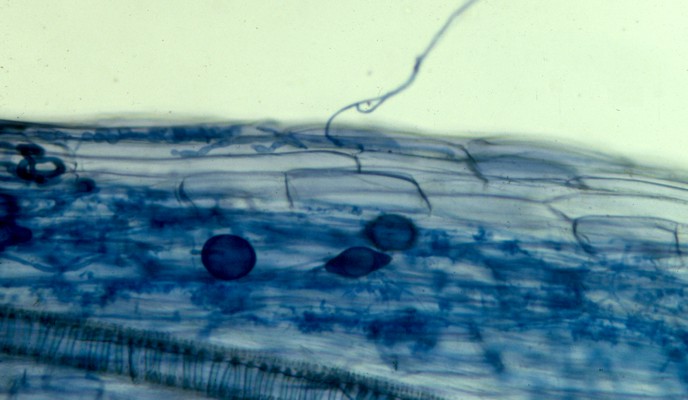

Arbuscules are simply highly branched hyphae that act as the point of transfer for substances passing back and forth between fungus and plant. Both organisms benefit, so this is a genuine form of mutualism. The picture at left shows part of a root of an onion plant. The root was boiled in potassium hydroxide for an hour to remove the cell contents from both plant and fungus, washed, acidified and then stained with a dye called Trypan blue. After this treatment only the cell walls of the plant and the fungus stain blue; without the treatment every part of the root would have taken on a deep blue colour and few details would have been visible. The fungus, staining more darkly than the plant, can be seen throughout the root. Only about half of the thickness of the root is included in the picture. You can tell this because the spring-like structure at bottom is the water-conducting part of the plant and is located at the centre of the root. Just outside the centre of the root are many indistinct or fuzzy blue areas. These are the arbuscules of the fungus, these site of nutrient transfer. The balloon-like cells are called vesicles and are structures used by the fungus for the storage of nutrients and also for long-term survival. The outermost cells of the root contain some more hyphae, remnants of the early colonization of the root by the fungus. Finally we see a fungal hyphae extending out away from the root where it was taking up nutrients from the soil. The nutrients, mainly phosphorus and nitrogen, taken up by the fungus from the soil, and the sugars produced by the plant via photosynthesis represent the "currency" used by each of the partners in maintaining a mutualistic rather than parasitic relationship.

Arbuscules are simply highly branched hyphae that act as the point of transfer for substances passing back and forth between fungus and plant. Both organisms benefit, so this is a genuine form of mutualism. The picture at left shows part of a root of an onion plant. The root was boiled in potassium hydroxide for an hour to remove the cell contents from both plant and fungus, washed, acidified and then stained with a dye called Trypan blue. After this treatment only the cell walls of the plant and the fungus stain blue; without the treatment every part of the root would have taken on a deep blue colour and few details would have been visible. The fungus, staining more darkly than the plant, can be seen throughout the root. Only about half of the thickness of the root is included in the picture. You can tell this because the spring-like structure at bottom is the water-conducting part of the plant and is located at the centre of the root. Just outside the centre of the root are many indistinct or fuzzy blue areas. These are the arbuscules of the fungus, these site of nutrient transfer. The balloon-like cells are called vesicles and are structures used by the fungus for the storage of nutrients and also for long-term survival. The outermost cells of the root contain some more hyphae, remnants of the early colonization of the root by the fungus. Finally we see a fungal hyphae extending out away from the root where it was taking up nutrients from the soil. The nutrients, mainly phosphorus and nitrogen, taken up by the fungus from the soil, and the sugars produced by the plant via photosynthesis represent the "currency" used by each of the partners in maintaining a mutualistic rather than parasitic relationship.

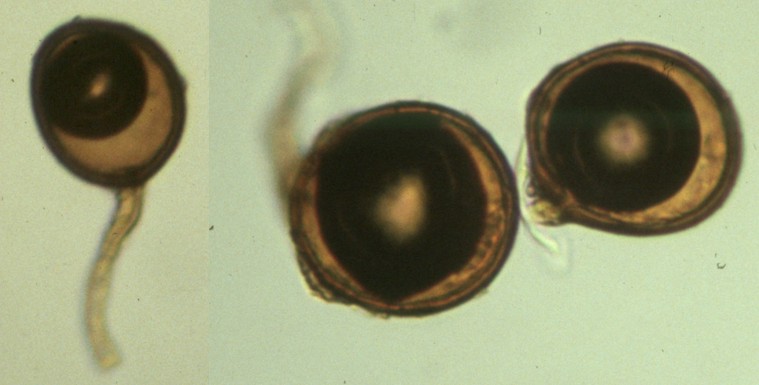

Mycorrhizae formed by Glomeromycota are found in the majority of land plants. Not surprisingly their spores are not very difficult to find in soil. These spores are larger than most fungal spores and can often be found using a low-power dissecting microscope. The ones in the picture at left are fairly small examples, being hardly more than 50 micrometers in diameter. They were collected by shaking a small sample of soil in a container and then examining the floating particles skimmed from the surface. Each spore contains an air bubble, suggesting that they were probably dead when they were collected. Larger live spores are often collected by passing a wet soil through a set of filters so that the different sizes of spores are trapped on the various mesh sizes.

Although their diversity is low there are several genera of Glomeromycota. These are distinguished on spore size, method of attachment to their hypha and number. Some species are able to form "sporocarps". These are compound structures formed from aggregations of many spores. Sporocarps are often adpted to being dispersed by rodents and are large enough to be of interest to these animals, who eagerly dig them up and consume them. The spores are later deposited in the animal's droppings in a new locality. Examination of the droppings of flying squirrels and certain other rodents often yields large numbers of glomeromycetan spores. These fungi superfically resemble truffles and false truffles in their ecology but are quite unrelated.