Home >> Diversity and classification >> True fungi >> Dikarya >> Ascomycota >> Discomycetes >> Operculate Discomycetes >> Truffles

TRUFFLES

The image at right shows the sessile operculate discomycete Sarcosphaera coronaria. It is common in coniferous forests of the Rocky Mountains and areas further west and is only rarely reported in the east. It also occurs in Europe but is rare and has been put on the Red List (endangered species) in 14 countries. It is particularly characteristic of old forests and is threatened by clearcutting and other intensive activities. It is NOT a truffle.

Sacrcosphaera coronaria is an unusual operculate discomycete due to its habit of producting its apothecia underground where they remain closed until the ascspores are mature. When that occurs the apothecia break open at soil level and the ascospores can be released forcibly in the manner of a typical cup fungus. The areas where it is common are often places where the forest floor is exposed to dry air. It is thought that by growing submerged in the soil it is able to avoid desiccation. Its significance to our discussion is that some members of the operculate discomycetes appear to have carried this strategy to a greater extreme and have apothecia that remain buried in the soil without breaking open and without forcibly discharging their ascospores. When this occurs the fungus can be called a truffle.

The fungus at left is Gilkeya compacta, a species of truffle occurring in mixed woods in Orgegon and California where it forms mycorrhizae with certain trees. It lives out its life beneath the ground and does not open when its ascospores are mature. In spite of its typically truffle lifestyle it retains many of the features of its discomycetous ancestors. The broken apothecium clearly shows that it is hollow and resembles ordinary operculate discomycetes. Under a microscope the asci are seen to line the sides of the apothecium and to be cylindrical, both features of a species that forcibly discharges its ascospores. However, G. compacta cannot shoot its ascospores; instead the asci dissolve or just remain intect at maturity. Since the apothecia and ascospores remain underground this species must use a medium other than air for the dispersal of its spores, and like other truffles it has turned to animals to to do the job. The apothecia produce an odour that is attractive to small mammals, mostly rodents, who dig them up and consume them. This arrangement works so well that some mammals such as flying squirrels subsist largely on truffles. Thus Gilkeya compacta and most other truffles have two forms of mutualism, one via mycorrhizae with trees and one with animals for ascospore dispersal.

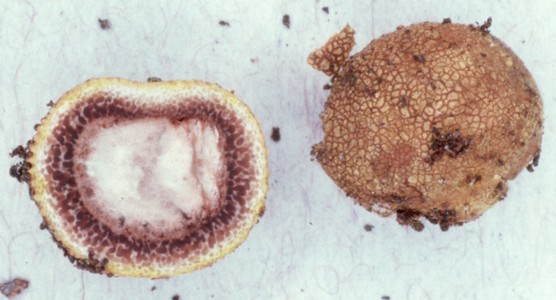

The species of Tuber in the photo at left shows a much more complex structure. Here the white layers of tissue bearing the asci are intricately folded throughout the fruiting body (it's hard to call that an apothecium) and thus occupy the entire space within. When the asci mature the dark ascospores completely fill the inside. The enlargement in the right panel is of a mature fruiting body, cut in half to show the white ascus-bearing tissues and the brown colour of the mature mass of ascospores. Tuber species are typical truffles in that they require animals for their dispersal. The genus Tuber is also notable because it contains some species that are eagerly sought for the table, particularly T. melanosporum, the black Périgord truffle, and T. magnatum, the white or Alba truffle. These species occur naturally in southern Europe and are now cultivated in other parts of the world as well. Since both species are mycorrhizal with oaks, cultivation requires growing both the oak and the fungus. The species at left, collected under aspen trees in northern Ontario, is not one of the famous ones.

The species ilustrated at right differs from the other truffles on this page in not being related to operculate discomycetes. This is a species of the genus Elaphomyces, a group of subterranean, rodent-dispersed fungi that forms mycorrhizae with forest trees. Recent genetic studies have revealed that Elaphomyces species are actually plectomycetes belonging to the Eurotiales.