Home >> What fungi are >> Reproduction >> Asexual Reproduction >> Asexual sporangia

FUNGI REPRODUCING ASEXUALLY BY MEANS OF SPORANGIA

Sporangiospores are spores that are produced in a sporangium (plural: sporangia). A sporangium in fungi (but not mosses and some other organisms) is simply a cell containing spores. We encounter this term in our discussion of sexual reproduction in the Chytridiomycota and Zygomycota and see that a sporangium can be the site of meiosis or mitosis. The important point is that a sporangium is a cell that encloses its spores until they are mature and ready for dispersal.

Asexual sporangia are commonly produced by the Chytridiomycota and Zygomycota. Although some similar structures, such as asci, are produced by members of the Dikarya they are never called sporangia and instead have their own special terms.

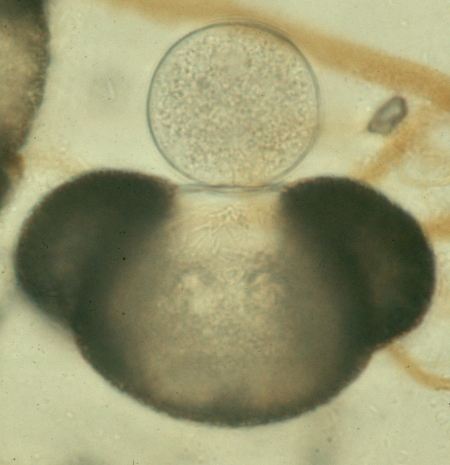

The picture at right is the same one used in our discussion of sexual reproduction, except that it was photographed using bright-field rather than phase-contrast optics. It depicts a species of Rhizophidium, a member of the Chytridiomycota, growing on the upper surface of a grain of pine pollen floating in a pond. This individual is typical of many chytrids in its simplicity; the sporangium is essentially the whole fungus. It started to grow on the pollen grain when a spore landed there and became attached by rhizoids, seen as faint threads extending into the pollen grain. The developing spore swelled to form the spherical sporangium and its nucleus divided numerous times by mitosis until the sporangium became filled with nuclei. Each nucleus then became surrounded by a spore wall. At the time the photograph was taken the sporangium was filled with spores, faintly seen in the picture as an internal granularity. If it had been allowed to develop further the sporangium would have developed an exit tube through which the sporangiospores could escape. The sporangiospores of Rhizophidium have whip-like flagella, allowing them to swim off in search of new sources of food. Because of their motility the sporangiospores of the Chytridiomycota require liquid environments, or at least water films. Because they are asexual, these sporangia can develop quickly and produce large numbers of offspring, each of which can swim off and colonize a new pollen grain, soon producing even more progeny. Some species of Chytridiomycota produce more than one sporangium, and these remain connected by thin hypha-like threads.

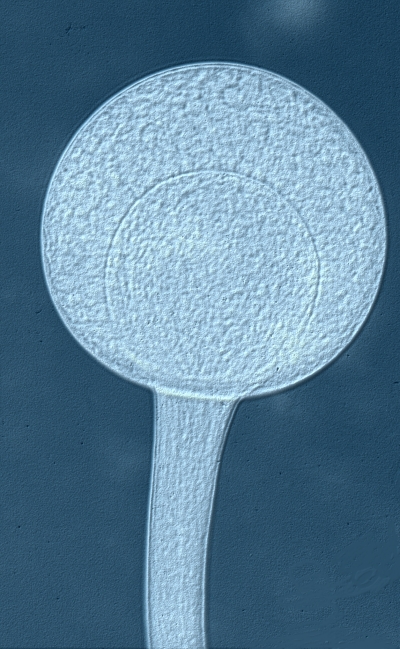

The Zygomycota are terrestrial organisms producing non-motile sporangiospores. The sporangia in this group are usually at the tips of specialized hyphae called sporangiophores. Probably the most difficult feature of the zygomycotan sporangium for most students to understand is the bulb-like structure called a columella. The columella is simply the end of the sporangiophore, enlarged so that it extends up into the sporangium. The picture of Rhizopus domesticus at near-left shows these relationships fairly well. The columella can be seen as a spherical body inside the large spherical sporangium. If you examine the photo carefully you will see where the columella connects to the sporangiophore on the right side. The spores inside the sporangium surround the columella but are never inside it. The photo at far-left shows a sporangiophore of Absidia spinosa. Here the sporangium has ruptured and released all of its spores. What is left is the sporangiophore topped by a columella, with the remnants of the sporangial wall remaining as a cup. The columella of Absidia spinosa, and that of some other Zygomycota as well, is characterized by the presence of an apophysis, a small pointed extension on its upper surface. It is these "naked" columellae, free of the sporangium and spores, that cause beginners so much confusion. They give the appearance of being immature sporangia, and may be interpreted as such if intact sporangia are not present. Of course some Zygomycota produce sporangia without a columella, but these are usually fairly easy to recognize.