Home >> Diversity and classification >> True fungi >> Dikarya >> Ascomycota >> Plectomycetes >> Plectomycetes with pyrenomycetous origins

PLECTOMYCETES WITH PYRENOMYCETOUS ORIGINS

Many cleistothecial fungi appear to have similaries to pyrenomycetes. Some of these similaries indicate rather obvious relationships, such as Chaetomidium subfimeti and Sphaerodes fimicola illustrated at left, generally recognized as members of the Melanosporaceae and Chaetomiaceae even without genetic evidence. The transformation from typical pyrenomycete to plectomycete may involve several evolutionary steps and with each of these steps yielding viable competitive species.

The environmental incentives leading to the evolution of a plectomycete are probably many. One of these may be the availability of suitable nutrients in an environment where forcible ascospore discharge is futile, such as under the bark of a dead tree or the centre of a compost pile. In these situations there would be no penalty to a fungus that lacked forcible spore discharge and in fact some advantage to it in terms of energy savings through simplification of its structures. Once forcible ascospore discharge is lost there might be other changes such as elimination of the ostiole. If there is no ostiole it might be more efficient to pack more asci into the centrum by making them spherical and uniformly distributed. Of course this is all speculation, but we do know that there are species living today that appear to occuply places along this evolutionary road and that those close to the beginning are easier to connect to ostiolate relatives than those further along. Thus Sphaerodes fimicola and Chaetomidium subfimeti lack perithecial ostioles yet retain the arrangement of asci found in ostiolate species. Their asci are clustered at the bottom of the cleistothecium and directed up toward an ostiole that isn't there.

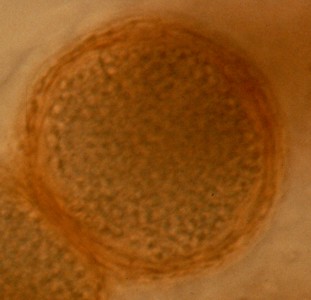

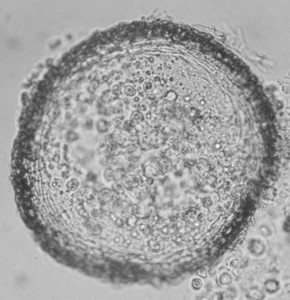

Some cleistothecial fungi are more difficult to assign to their proper group because they lack almost all the distinguishing features of their ancestors. The two species at right, Hapsidospora irregularis and Leucosphaerina arxii, both have spherical cleistothecia, no ostioles, uniformly distributed spherical asci and small single-celled ascospores. Both have Acremonium asexual stages. They differ from one another in at least two ways: H. irregularis has dark cleistothecial walls and dark roughened ascospores while L. arxii has orange cleistothecial walls and light-coloured smooth ascospores. Genetic studies have now shown that these species both belong to the Bionectriaceae, a fairly large family in the Hypocreomycetidae containing several genera of highly simplified cleistothecial fungi with Acremonium stages.

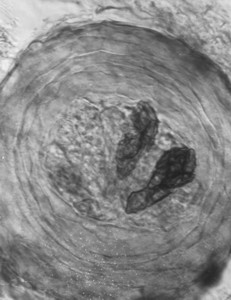

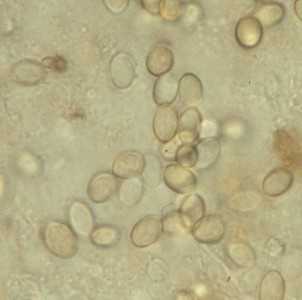

Although several plectomycetes can trace their origins to the Bionectriaceae others have different beginnings. The next three pictures are of members of the Microascaceae, another family in the Hypocreomycetidae. Although uniformly lacking forcible ascospore discharge many of the Microascaceae do have ostiolate perithecia. However, species of Pseudallescheria and Kernia are entirely cleistothecial. The cleistothecia and ascospores at left are of Pseudallescheia boydii, a species common in soil and compost. The cleistothecia have been broken open so the asci would come out. It is similar in appearance to some quite unrelated fungi but can be recognized by its brown ascospores that have small germination pores at the poles. These ascospores are strongly dextrinoid in Melzer's solution when they are young, a feature common to all Microascaceae.

The photo at left is of Kernia nitida, a species found on dung and in the nests of rodents and other animals. Its ascospores are similar to those of Pseudallescheria. The long hooked hairs on the cleistothecium are thought to catch in the fur of rodents, allowing the cleistothecium to be dispersed. Beside the characteristic ascospores, members of the Microascaceae can be recognized by their asexual stages belonging to Scedosporium and Scopulariopsis.

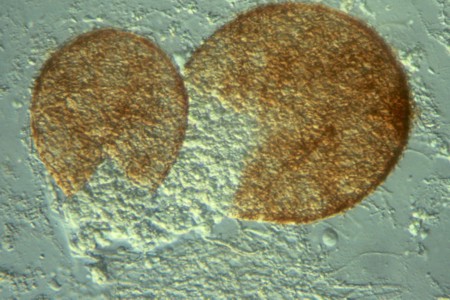

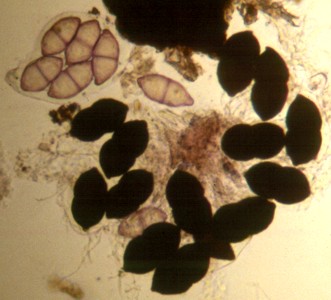

All of the examples above have been of members of the Sordariomycetes, but other plectomycetes can trace their roots to the Dothideomycetes. One of these with interesting roots is Zopfia rhizophila which produces its cleistothecia on the moribund roots of asparagus plants. It has among the largest ascospores of all plectomycetes. Those in the picture at right are more than 60 µm (micrometers) in length. This one is easy to find; just locate an old asparagus plant, dig it up and examine the semi-dead roots for large black cleistothecia. Neither new healthy roots nor long-dead ones will yield many cleistothecia. There are several species of Zopfia, all on roots and all with huge ascospores. Zopfia albiziae is found on the roots of Albizia lebbek, the East Indian Walnut, and produces the largest ascospores in the genus, which attain a length of 135 µm. Species of Zopfia are thought to be related to the ostiolate species Caryospora putaminum, a species found on old peach pits and producing similar large two-celled ascospores.

Phaeotrichum hystricinum, the fungus illustrated at left, is another member of the Pleosporales producing cleistothecia. It occurs on the dung of North American porcupines but only when the dung has been piled up. North American porcupines often occupy dens under large rocks or near the base of hollow trees. One den in Ontario, from which the first collection of P. hystricinum was made in the 1950's, was still occupied thirty years later and still produced P. hystricinum. Living in such a den creates certain sewage-disposal problems. Porcupines deal with this by shoving the dung out the entrance of the den where it collects in large piles. These dung piles support a great variety of cleistothecial fungi, including P. hystricinum. Of course when the porcupine is out foraging it may also need to defecate, but these isolated pieces of dung rarely yield plectomycetes. Apparently these fungi are resident in the dung piles and do not enter the gut of the animal in the manner of many coprophilous fungi.