Home >> Diversity and classification >> True fungi >> Dikarya >> Basidiomycota >> Agaricomycotina >> Non-gilled macrofungi >> Pore fungi

PORE FUNGI

Polyporus squamosus, in the picture at right, is a quintessential "polypore", with its mushroom-like cap, undersurface composed of fine pores and its growth habit on the side of a tree. This one was growing on a living Norway maple in a Toronto neighbourhood, probably living off parts of the tree that had previously died. Polyporus squamosus is a member of the order Polyporales, a fairly modest group of species causing "white rot" of a variety of trees.

The pore fungi, including P. squamosus have their basidia lining the inner walls of tubes that are bound together into a honeycomb-like tissue as shown at left. This picture was not taken directly above the pores, so they appear to be shallow or blocked, but they really extend several millemeters in. The entire basidioma is able to respond to gravity and align its tubes precisely perpendicular to the earth so that the spores will fall out without sticking to the walls. Many members of the Basidiomycota exhibit such geotropisms (responses to gravity) and will sometimes re-orient themselves even after they are removed from their substrate. Species of the mushroom genus Amanita are especially adept at this. When you look at a large fungus like P. squamosus, with its hundreds or maybe thousands of minute spore-bearing tubes, it is nothing short of amazing that it is able to set all of these to a precise perpendicular alignment. Clearly these are very sophisticated organisms.

Although P. squamosus has a stipe (stalk) and a mushroom shape not all pore fungi do. Some are so simple in appearance that they resemble one of the resupinate corticioid fungi, differing only in having pores. Others may lack a stipe altogether and form simple brackets on their substrate. Some, such as Laetiporus sulphureus at left form large brackets in overlapping clusters. In general, the overall appearance of a pore fungus is not a very good indicator of its true relationships to other fungi.

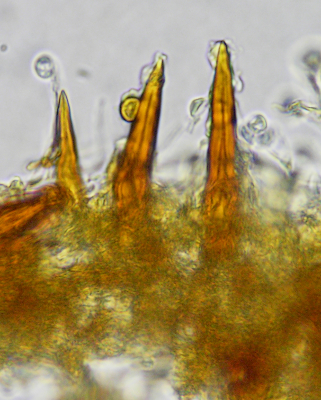

Poroid members of the order Hymenochaetales, pictured above, account for many species having a brown context (flesh). Inocutis rheades, at left, is typical of this group in forming simple shelving brackets on poplar logs. Coltricia perennis at right is unusual, being a stipitate member of the Hymenochetales. Many Hymenochaetales have red spines that protrude out among the basidia as illustrated for the stereoid genus Hymenochaete and for Inonotus below.

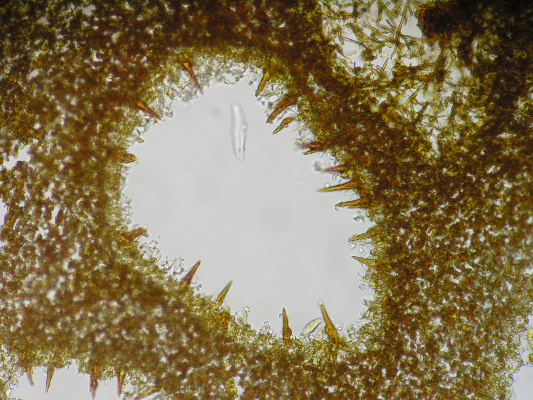

The pictures above are of Inonotus cuticularis, a common member of this genus growing on maple and other hardwood trees, in this instance mountain ash. The panel at far left shows the basidiomata growing on the tree. The middle is taken from a cross section across the pore layer. The setae extending inro the centre of the pore are typical of the family Hymenochaetaceae, to which Inonotus belongs. The right panel is a closer view. One could imagine these setae would discourage small herbivores from entering a pore and damaging the basidia and basidiospores but we really don't know enough about the ecology of these fungi to confirm such a suggestion.

Some of the poroid fungi become quite large and woody and may persist for several seasons. Pictured above are two of these, Fometopsis pinicola, a species commonly found on coniferous trees and Ganoderma applanatum an inhabitant of dead deciduous trees. Both of these species remain for several seasons and produce a new layer of tubes each year, thus getting larger and larger. The third panel shows a basidioma of G. applanatum that has been cut open to reveal three layers of tubes, representing three years of growth. Since the new tubes are added each season below new marginal growth as well as over the old tubes the thickest part of the basidioma will be near the point of attachment to the tree.

Some of the pore fungi have pores that become elongated or irregular in outline or even resemble mushroom gills. Daedalia quercina, the species at right, has a pore surface that is often described as "labyrinthine" or "daedalioid". The generic name Daedalia was named in honour of Daedalus, a famed architect in Greek mythology who constructed a remarkable labyrinth on Crete to contain the minotaur. The pair of closeup photos shows the variation in the pore surface of Daedalia quercina. Even though the bottom panel is rather out-of-focus it is easy enough to see just how labyrinthine these can become.

Finally we come to the most extreme example of a mushroom-like pore fungus. This species, Lenzites betulina, a common inhabitant of dead birch logs, has its tubes so elongated they resemble gills. The photos show the upper surface at left and the underside at right. The thick and slightly branched gills are a clue to their pore-bearing relatives.

Roy Cain's Field Key To Polypores, on our pages, will be some help in identifying pore fungi in eastern Canada and adjacent parts of the United States. Dr. J.H. Ginns has published a wonderful book on the Polypores of British Columbia, downloadable as a PDF file, that is a valuable resource for the western part of North America. Many of the species in his book can be found throughout the temperate regions of the world.