Home >> Diversity and classification >> True fungi >> Dikarya >> Ascomycota >> Hemiascomycetes

"HEMIASCOMYCETES"

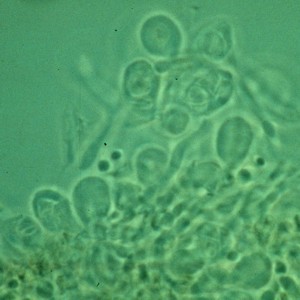

The term "Hemiascomycetes" is a very old-fashion one used to designate certain groups of Ascomycota having asci that are not organized into any kind of fruiting body. Included in this group are yeasts, extremely simple single-celled fungi that convert their one and only cell into an ascus. The definition can the be extended to include the partially hyphal Endomyces decipiens, a species that grows on the lamellae (gills) of Armillaria mushroms.

More recent work in mycology has shown that simplicity of structure is not always a good indicator of relationships and that the old Hemiascomycetes would have to share their position with some more complex species. Because of this it is no longer possible to define these groups very precisely based only on their appearance. Instead we have several classes of fungi, the Taphrinomycetes, the Neolectomycetes, the Pneumocystidiomycetes, Schizosaccharomycetes and the Saccharomycetes that lie outside the major subphyla. These classes are not necessarily closely related to one another but it is convenient to regard them here in one place.

The Taphrinomycetes

The Taphrinomycetes are obligate plant parasites that usually cause brightly-coloured tumor-like growths on plants. The picture above shows three species of Taphrina (L to R): T. deformans, T. johansonii and T. robinsoniana. Taphrina deformans is a parasite of peach trees causing a disease called "leaf-curl". The disease, which can affect both leaves and fruit, becomes established in the spring as the new leaves emerge, sometimes causing them to drop prematurely. The asci are borne in open exposed layers on the red swellings. Taphrina johansonii occurs on catkins (flower clusters) of trembling aspen, causing them to enlarge abnormally and take on a bright yellow colour. Taphrina robinsoniana is a parasite of speckled alder. It attacks the cone-like catkins and causes their scales to enlarge into long red tongues bearing asci. Ascospores of Taphrina species germinate readily and will grow in the laboratory to form yeasty colonies but will never produce asci and ascospores

The Neolectomycetes

Neolecta, above and at left, has become one of the great surprises of modern mycology and a delight to all who are familiar with it. Drs. Sara Lanvik, Ove Eriksson, Andrea Gargas and P. Gustafsson, working on DNA sequences in Sweden in 1993, discovered that species of Neolecta were only very distantly related to other Ascomycota. Their work revealed these fungi to be near the very bottom of the evolutionary tree of the ascomycetes. Drs. Landvik, Eriksson and Dr. Mary Berbee at the University of British Columbia later referred to these species as "fungal dinosaurs" and "living fungal relics of the past". The reason this was so surprising to mycologists was that no one expected a fairly large multicellular organism to be near the bottom of the tree; it was long thought that certain yeasts occupied all such territory. So these formerly humble little species are now regarded with great awe.

|

OLDER AND BIGGER Prototaxites loganii, known from 400 million-year-old fossil material, has long been suspected of being a fungus. Dr. Francis Hueber working at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. published a detailed account of this species in 2001 maintaining that it had all the features of a fungus and assigned it to the group we now call the Agaricomycotina (mushrooms and their allies). In May, 2007 Dr. C. Kevin Boyce of the University of Chicago and several colleagues (including Dr. Hueber) published geochemical evidence indicating P. loganii to be saprotrophic, thus supporting its placement among the fungi. In 2014 Drs. G.J. Retallack of the University of Oregon and Ed Landing of the New York State Museum presented evidence that P. loganii was indeed a fungus, was possibly lichenized and might best be assigned to the Glomeromycota. The most amazing thing about P. loganii is that it formed structures up to eight meters high and dwarfed all other vegetation. Species of Neolecta, if they were around then, would have been miniscule in such a forest. Late in 2017, Rosemarie Honegger and co-authors, studying another species of Prototaxites, P. taiti, examined remarkably preserved fossil material bearing what they concluded to be apothecia with asci and paraphyses. They argued that this species is similar to members of the Neolectomycetes, a class containing only species of Neolecta. They were unable to find evidence indicating whether it was mutalistic, parasitic or saprotrophic. |

Mycologists recognize three species of Neolecta, N. irregularis, top photo, N. vitellina, bottom photo, and N. flavovirescens (not shown here). The first two species are both common in Canada; N. flavovirescens occurs in tropical forests. The biology of Neolecta species is still poorly understood. Dr. Scott Redhead, Canada Agriculture, Ottawa, has shown that the ascomata of N. vitellina can be traced underground to a connection with spruce roots, leading him to suggest that they are weak root parasites. Other than that we know very little about Neolecta.