|

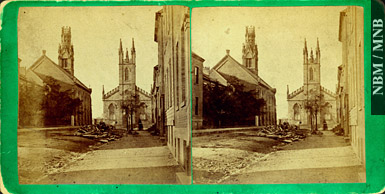

Double Vision: New Brunswick Stereographs 1865-1880

Using mid-nineteenth century scientific insights into the nature of light and optics, combined with an appropriate viewing apparatus, a dramatic illusion of depth and perspective is reproduced by the stereograph. This startling three-dimensional effect, which in some cases is even more apparent than that regularly experienced by ordinary sight, is captivating. To create it, two small, almost identical photographs are mounted side by side and when seen through a special viewer, the perception of three dimensions occurs as the brain fuses into one image, the separate images that each eye sees. Using mid-nineteenth century scientific insights into the nature of light and optics, combined with an appropriate viewing apparatus, a dramatic illusion of depth and perspective is reproduced by the stereograph. This startling three-dimensional effect, which in some cases is even more apparent than that regularly experienced by ordinary sight, is captivating. To create it, two small, almost identical photographs are mounted side by side and when seen through a special viewer, the perception of three dimensions occurs as the brain fuses into one image, the separate images that each eye sees.

From their first introduction in the 1840s, stereographs provided a novel form of entertainment for an enthusiastic public.

The apex of the stereograph's popularity was the period 1865 to 1880. During these fifteen years, photographers and publishers produced millions of these photographic views. No exception in New Brunswick, stereographs enjoyed a surge in popularity after their introduction in the late 1850s. One of the first advertisements for them in the province appeared in the New Brunswick Reporter . The apex of the stereograph's popularity was the period 1865 to 1880. During these fifteen years, photographers and publishers produced millions of these photographic views. No exception in New Brunswick, stereographs enjoyed a surge in popularity after their introduction in the late 1850s. One of the first advertisements for them in the province appeared in the New Brunswick Reporter .

Placed by George Stacy, an itinerant photographer active in Fredericton, the announcement in the 17 July 1857 notice read:

SOMETHING NEW

JUST RECEIVED AT STACY'S AMBROTYPE ROOM,

IN COY'S BUILDING OVER LEMONT'S STORE

A few Stereoscopes, also a large addition to his stock of cases and frames, which is now the largest and best selected ever offered in this place. The Stereoscope is one of the most wonderful recent discoveries. Those who have not yet seen them should not fail to avail themselves of the present opportunity. Ladies and Gentlemen are respectfully invited to call in and examine specimens.

Although many of the most popular stereoscopic views were those imported from Europe and the United States, New Brunswick scenes were being produced by local photographers. The existing stereographs of provincial scenes can be analyzed and placed into a more accurate perspective, one that helps to document the development of some of the provinces, urban centers, and as well, affords a glimpse into social realities and the perceptions of those who made the images. Photography in the province was, almost exclusively, a commercial enterprise. The real impetus was the entrepreneurial spirit of nineteenth century commercial photographers who felt that to survive, they must expand their business to include alternatives to basic portraiture. While the invention of new processes created the ability to produce vast amounts of images at reasonable prices, unfortunately, for photographers, it also produced a situation where they were dependent upon the public to buy more and more images. Stereograph photographs enabled them to increase their studio output and offer merchandise rivaling that of their competition. As the frequent economic recessions of the nineteenth century remind us, acumen be Although many of the most popular stereoscopic views were those imported from Europe and the United States, New Brunswick scenes were being produced by local photographers. The existing stereographs of provincial scenes can be analyzed and placed into a more accurate perspective, one that helps to document the development of some of the provinces, urban centers, and as well, affords a glimpse into social realities and the perceptions of those who made the images. Photography in the province was, almost exclusively, a commercial enterprise. The real impetus was the entrepreneurial spirit of nineteenth century commercial photographers who felt that to survive, they must expand their business to include alternatives to basic portraiture. While the invention of new processes created the ability to produce vast amounts of images at reasonable prices, unfortunately, for photographers, it also produced a situation where they were dependent upon the public to buy more and more images. Stereograph photographs enabled them to increase their studio output and offer merchandise rivaling that of their competition. As the frequent economic recessions of the nineteenth century remind us, acumen be yond the ordinary was required to succeed in business, for the photographic industry was especially susceptible to reduced patronage in difficult times. Satisfying the whims of the public, the variety of subjects which stereographs present indicate the extent to which photographers succeeded at whetting the public's desire to experience contemporary historic, political and natural events. In effect, these stereographs were the first form of photo-journalism, and gave people a more complete understanding of their country and the world. In retrospect, what was used primarily as an amusement can now be considered a trove of authentic information that allows present-day historians to ascertain many facts about the early development of many towns and cities as well as the activities and interests of their citizens. yond the ordinary was required to succeed in business, for the photographic industry was especially susceptible to reduced patronage in difficult times. Satisfying the whims of the public, the variety of subjects which stereographs present indicate the extent to which photographers succeeded at whetting the public's desire to experience contemporary historic, political and natural events. In effect, these stereographs were the first form of photo-journalism, and gave people a more complete understanding of their country and the world. In retrospect, what was used primarily as an amusement can now be considered a trove of authentic information that allows present-day historians to ascertain many facts about the early development of many towns and cities as well as the activities and interests of their citizens.

The lack of original source materials from the studios and insufficient biographical material on the photographers allow only a prefatory evaluation of the finer details of stereographic development in New Brunswick. In some cases, stereographs were pirated; labels from a New Brunswick photographer's studio sometimes were adhered to stereographs which originated in England or the United States. Correct attribution of unidentified stereographs to a particular photographer is hampered by the practice of purchasing negatives from competitors as they went out of business. The views were then assimilated into the holdings of the new studio under the name of the purchaser without credit being given to the original photographer. Saint John was home to the largest concentration of photographers in the province, consequently most New Brunswick stereographs represent Saint John scenes.

In a society not conditioned to the barrage of visual imagery that is presently taken for granted, the stereograph allowed the perception of being one step closer to reality. Where before there was only written documentation about a place or event, and sometimes the romanticized or inadequate rendering of a scene by an artist, the stereograph provided an inexpensive and convincing alternative. Containing more than a visual documentation of the province's pre-1880 history, these stereographs also offer an opportunity to understand the manner in which New Brunswick was perceived and presented in the nineteenth century. In a society not conditioned to the barrage of visual imagery that is presently taken for granted, the stereograph allowed the perception of being one step closer to reality. Where before there was only written documentation about a place or event, and sometimes the romanticized or inadequate rendering of a scene by an artist, the stereograph provided an inexpensive and convincing alternative. Containing more than a visual documentation of the province's pre-1880 history, these stereographs also offer an opportunity to understand the manner in which New Brunswick was perceived and presented in the nineteenth century.

|