Home >> Diversity and classification >> True fungi >> Dikarya >> Basidiomycota >> Agaricomycotina >> Gasteromycetes >> Puffballs

PUFFBALLS

Bovista plumbea, at left, is a familiar fungus and one that we could call a typical puffball. It commonly appears in lawns and fields where it matures and gradually loses its white outer layer, revealing a papery lead-coloured layer beneath. When the papery layer is broken the basidiospores escape in a smokey cloud. Usually the mature basidiomata of B. plumbea break loose from their attachment to the soil and get blown or kicked around, releasing their spores with every jolt. Although seldom larger than a golf ball these basidiomata can produce astounding numbers of spores, perhaps millions. With such powers of reproduction it is not surprising that this species can be found in most lawns.

Some puffballs remain attached to the soil at maturity. Calvatia cyathiformis, at right, has a large sterile base and is thick-walled in the lower parts so that at maturity it is like a goblet full of dry spores. These dry basidiomata can still be seen in the ground long after the spores are gone.

Calvatia cyathiformis is fairly large and conspicuous but is nevertheless of only modest size compared to some puffballs. In fact, some puffballs are among the largest fungi known. The picture at left is of Calvatia gigantea, but this particular specimen is quite small for its species. Basidiomata the size of basketballs are found regularly and even larger ones are sometimes collected. William Coker and John Couch in their 1928 book The Gasteromycetes of Eastern United States and Canada cite a record of a puffball collected in New York State in 1877 that measured 5.3 X 4.5 X 6.8 feet (1.6 X 1.4 X 2.1 meters). In his classic series Researches on Fungi Professor Arthur Henry Reginald Buller estimated that a giant puffball 40 X 28 X 20 cm would contain more than 7 trillion basidiospores. No one has attempted to confirm his estimate with a direct count!

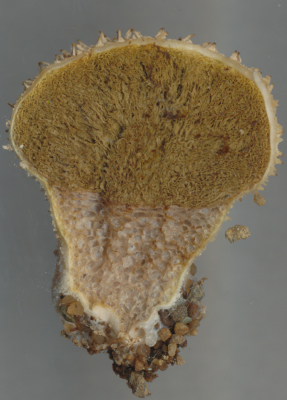

All of the puffballs discussed so far have been species that grow in open fields and depend upon wind and perhaps being stepped on to release their spores, but there are many that grow in forests where there is far less wind. These species often have a type of bellows mechanism that is operated by large drops of water falling from the branches of trees. One such fungus, Lycoperdon perlatum, is seen in the pictures above. It is fairly soft at maturity and has a pore through which the spores can escape when a drop hits the basidioma. A cross section of one of these puffballs at upper right reveals a soft chambered pedistal supporting a large cavity containing a dry mass of yellowish brown basidiospores (the gleba).

In discussing gastromycetes it must always be borne in mind that these fungi are not necessarily closely related. The features they possess are often the result of common ecological demands rather than ancestral traits. In spite of this ecological factor, some species really do share more recent common ancestry. Thus all of the puffballs discussed up to this point are thought to be members of the order Agaricales, the mushrooms.

The two fungi shown above are not members of the Agaricales, even though they seem to be similar. The main difference is that the gleba is enclosed within a membrane that is itself surrounded by a thick "rind". At maturity the rind splits open in a star-like fashion to reveal its contents. Such fungi are called "earth-stars". Geastrum triplex, at upper left, is related to the stinkhorns, although it lacks the unpleasant odour of most of that group and does not depend upon insects to disperse its basidiospores. Like the stinkhorns, it is a saprotrophic decomposer of plant litter. Astraeus hygrometricus, upper right, is an ectomycorrhizal fungus associated with the roots of certain plants growing in sand. Unlike the amazingly similar G. triplex, it is a member of the Boletales and is only a distant relative to it. It is classified in the Sclerodermataceae, a family deserving further comment.

The Sclerodermataceae is a small but interesting family of the Boletales. Although they belong to the order Boletales they are certainly not typical boletes. The picture above shows some views of Scleroderma citrinum a species forming mycorrhizae with with both conifers and hardwoods. The leftmost two, one cut open to show the spore mass in the gleba, were found in a coniferous forest in New Brunswick. Unlike the puffball members of the Agaricales, basidiomata of Scleroderma species are black inside, even when quite young. The spore mass is rather moist, firm and covered by a very thick rind. Although you might think such a basidioma hardly qualifies as a puffball it will, when mature, break open to release dry spores. The photo at right shows this same species growing in an ore roasting bed in Sudbury, Ontario splitting open to release its spores. Although this web site is not usually concerned with the edibility of fungi, it's important to point out that people collecting puffballs for the table should avoid ones with a black interior, since species of Scleroderma are known to be toxic.

Pisolithus tinctorius, a relative of Scleroderma, is unusual in having its spores produced within round, pea-like structures inside the basidioma. It forms mycorrhizae with a variety of trees and can grow under very stressful circustances, an ability that has attracted the attention of foresters who wish to introduce a mycorrhiza to trees that will allow them to grow on abandoned mine tailings and other harsh environments. It is known from many parts of the world and is generally most successful in warmer climates,