DISCUSSION OF THE PUCCINIOMYCOTINA

Although as many as 95% of the Pucciniomycotina are members of the Pucciniales there is nevertheless a diversity of forms that are not rusts. These fungi are so diverse that it is difficult characterize them other than to re-state that they are not rusts. Therefore the most convenient way to approach them is to define a rust.

A complete rust life cycle

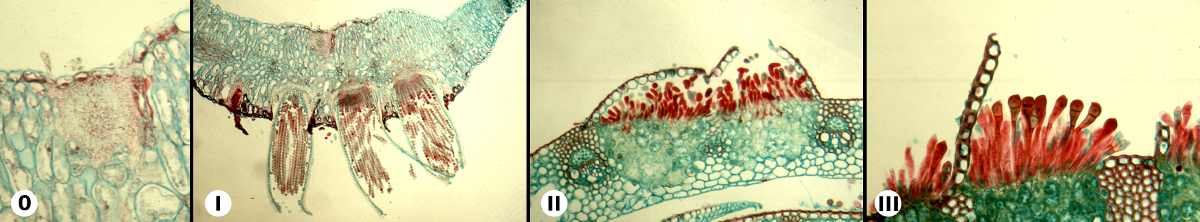

The numbered views above were photographed from microscope slides used for an introductory course in mycology. These slides are readily available from companies selling supplies for science classes. Students often find them dull and detached from the realities of the biological world, but in fact these slides have been professionally prepared from competently collected materials and clearly illustrate structures that would be difficult for a student to observe first-hand.

The fungus used for the slides is Puccinia graminis, the organism causing stem rust of wheat and many other grasses. It is a useful fungus for study because it is a rust having all of its stages and structures intact. Many of the Pucciniales have heteroxenous life histories, that is, they are parasites requiring more than one host species to complete their life cycle. The Pucciniales are a large enough group that specialists have developed a terminology for them separate from that used for other parasitic plants and animals. For their life histories uredinologists (rust specialists) have come to use the term heteroecious in place of heteroxenous, and autoecious instead of homoxenous. Puccinia graminis has two hosts, barberry (Berberis vulgaris) and wheat (Triticum aestivum) and must have both in reasonable proximity to complete its life cycle. In order to accomplish this cycling between two hosts it uses five different kinds of spores, traditionally designated with the numeric ciphers 0, I, II, and III. The Roman numeral IV has been used for basidiospores but this has never been widely accepted. Stages 0 and I occur on barberry while II, III and basidiospores are on wheat. Of course there is a special terminology associated with the numbered stages:

0 - Spermagonia and spermatia, often called pycnia and pycniospores in the older literature. This is a fertilization stage. The spermagonia are small flask-shaped structures that produce minute spermatia from special cells lining their interior walls. They are produced on the upper surface of barberry leaves in spring and soon produce enough spermatia that these are forced out through an opening and collect there in a drop of sugary fluid. The fluid is attractive to flies and other insects that visit the spermagonia to collect the "nectar". Thus the spermagonia, which contain a single haploid nucleus, are transported from leaf to leaf and ultimately fertilize the cells of another spermagonium. When this happens the dikaryon is established and the fungus can go on to the next part of its life cycle.

I - Aecia and aeciospores. Once a dikaryon has become established the hyphae grow down through the barberry leaf and begin to form aecia on its underside. Aecia are usually larger than spermagonia and are capable of producing large numbers of binucleate (dikaryotic) aeciospores, usually in long chains. Note that in the picture you can see a spermagonium on the upper surface and three aecia on the lower surface. The function of aeciospores is to infect the wheat plants as they emerge from the ground which is why the barberry and the wheat plants cannot be too distant from one another. The dry, powdery and extremely numerous aeciospores are carried by wind, or possibly by insects, to the wheat plants where they penetrate the surface tissues and begin to grow.

II - Uredinia and urediniospores. After the aeciospores land and infect the growing wheat plants the fungus begins a season-long period of growth and reproduction. Growth is in the stem of the wheat plant and reproduction is accomplished by means of uredinia, blister-like structures that develop under the plant's epidermis. The uredinia produce urediniospores which travel to other wheat plants and start new infections. Although only a few plants may have initially been colonized by aeciospores from the barberry it isn't long before these infect others of their kind through urediniospores. Infection may begin slowly in the spring but increases rapidly as the number of infected plants grows, each with the ability to infect others.

III - Telia and teliospores. Near the end of the growing season P. graminis begins to produce telia instead of uredinia. Although these are produced on the stem in much the same way as uredinia the spores they produce, the teliospores, are unable to infect other wheat plants. Instead they remain attached to the wheat or simply fall to the ground. Unlike urediniospores, the teliospores of P. graminis are two-celled, dark reddish brown and have very thick walls. Their function is to remain in the field throughout the winter in a state of dormancy. In the spring, before the wheat has begun to grow, the teliospores "germinate" to produce two basidia, each bearing four basidiospores. These basidiospores are dispersed in the air and, if they are successful, land on a developing leaf of barberry where they germinate to produce the new monokaryon. These developing monokaryons produce spermagonia, thus completing the annual cycle of the fungus.

The life cycle of P. graminis is a complete one, involving two hosts and five spore types. However, one of the most interesting features of the rusts is that many species exhibit modifications of this basic type, including the loss of one host and one or more spore types. The patterns that these modifications display and the ecological factors that influence them present a fascinating field of study. Although a great variety of modifications exist it is always possible to recognize a member of the rust fungi because at least one of the basic stages persists. No other fungi have these stages, which is the basis for saying that the best way to recognize one of the other members of the Pucciniomycotina is to see that it has none of the characteristic rust spore states. A rather deductive way to make an identification!