Home >> Diversity and classification >> True fungi >> Dikarya >> Ascomycota >> Pyrenomycetes >> Sordariomycetes >> Hypocreomycetidae >> Halosphaeriaceae

THE HALOSPHAERIACAE

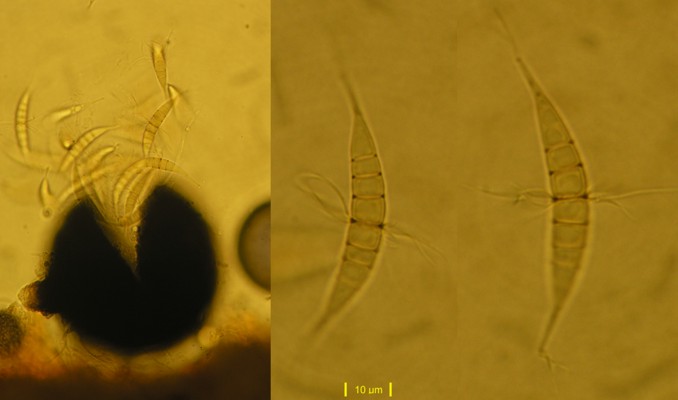

The Halosphaeriaceae are aquatic to semiaquatic marine fungi. Because of their aquatic habitats they do not forcibly eject their ascospores from the ascus. Instead the asci disintegrate at maturity, releasing the ascospores into the cavity of the perithecium. The spores then escape through the ostiole into the environment. Most species that have been studied seem to release their spores into the water, which then can drift to new substrata. This rather planktonic approach to spore dispersal depends upon a spore that will not sink rapidly and fall helplessly to the bottom. Most species have ascospores provided with gelatinous or hair-like appendages that extend well away from the wall. In the picture of a Corallospora at right the ascospores have a prominant ring of hair-like appendages at the middle and another set at each end. Species of Corallospora normally produce their ascospores in perithecia on sand above the low tide mark and these are easily found by examining sea foam. The hairs seem to aid not only in reducing the sink-rate of the spores but also seem to help them stick to bubbles in the foam. The perithecia themselves are dark and thick-walled. The one in the picture has been broken open to force out the ascospores within. Note also the little bump on the left side of the perithecium. In many Corollospora species the perithecia are firmly attached to sand grains with the ostiole pointed down or to the side where it is less likely to be blocked by a neighbouring sand grain.

Although the majority of Halosphaeriaceae have colourless ascospores with characteristic appendages there are a few exceptions. Species of the genera Nereiospora and Carbosphaerella have transversely septate ascospores typical of the family but with all but the end cells a smoky brown. All have appendages typical of the Halosphaeriaceae. On the other hand, species of the genera Nais and Luttrellia have typically colourless ascospores but without appendages.