|

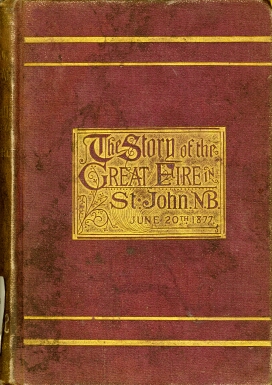

The Great Fire of Saint John, New Brunswick, 1877

In late June 1877, Saint John, New Brunswick, was laid waste by a devastating fire.

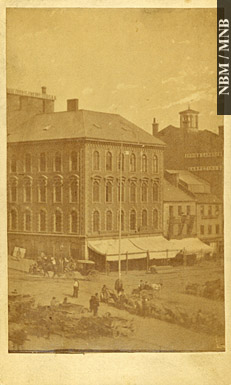

It began about 2:30 on the afternoon of 20 June when a spark fell into a bundle of hay in Henry Fairweather's storehouse in the York Point Slip area, which in present day is in the vicinity of Market Square. It is unknown where the spark originated. It may have come from McLaughlan & Son's boiler shop next door or may have been carried from a nearby sawmill. The month of June had been warm, with fine weather and little or no rain. Wooden structures predominant in Saint John at this time were tinder dry and highly flammable. When the fire was discovered it was already burning rapidly in large bundles of hay and aided by a fresh, strong breeze it rapidly escalated into a major conflagration. Within two minutes of the alarm sounding, Engine #3 was dousing the fire. Although other engines followed immediately, the fire had already spread by means of heat and sparks to other wooden structures nearby. At times, the fire reached temperatures perhaps so high some buildings exploded into flames without actual contact with the fire. This prompted fearful rumours that the fire was intentionally set. It began about 2:30 on the afternoon of 20 June when a spark fell into a bundle of hay in Henry Fairweather's storehouse in the York Point Slip area, which in present day is in the vicinity of Market Square. It is unknown where the spark originated. It may have come from McLaughlan & Son's boiler shop next door or may have been carried from a nearby sawmill. The month of June had been warm, with fine weather and little or no rain. Wooden structures predominant in Saint John at this time were tinder dry and highly flammable. When the fire was discovered it was already burning rapidly in large bundles of hay and aided by a fresh, strong breeze it rapidly escalated into a major conflagration. Within two minutes of the alarm sounding, Engine #3 was dousing the fire. Although other engines followed immediately, the fire had already spread by means of heat and sparks to other wooden structures nearby. At times, the fire reached temperatures perhaps so high some buildings exploded into flames without actual contact with the fire. This prompted fearful rumours that the fire was intentionally set.

When it was over, the fire had destroyed over 80 hectares (200 hundred acres) and 1612 structures including eight churches, six banks, fourteen hotels, eleven schooners and four woodboats in just over a nine hour period. Nearly all the public buildings, the principal retail establishments, lawyers' offices and all but two printing firms were burned in the inferno. To make matters worse, less than one fourth of the $28 million in losses was covered by insurance. When it was over, the fire had destroyed over 80 hectares (200 hundred acres) and 1612 structures including eight churches, six banks, fourteen hotels, eleven schooners and four woodboats in just over a nine hour period. Nearly all the public buildings, the principal retail establishments, lawyers' offices and all but two printing firms were burned in the inferno. To make matters worse, less than one fourth of the $28 million in losses was covered by insurance.

Nineteen people died as a direct result of the fire and there were an undetermined number of injuries. While some people managed to save a few of their possessions, many residents and business owners lost everything they owned. Starvation and disease threatened as nearly all the food and medical supplies were destroyed when the business and warehouse districts burned. Shelter was an urgent need. Although several thousand people moved to nearby Portland or simply left the Saint John area altogether, a considerable number of city residents had nowhere to go. The Victoria Skating Rink on City Road served as a temporary shelter for several days. Tents were erected on the Barrack Green and shanties were rapidly erected on King Square and Queen Square as homes for people and businesses. Nineteen people died as a direct result of the fire and there were an undetermined number of injuries. While some people managed to save a few of their possessions, many residents and business owners lost everything they owned. Starvation and disease threatened as nearly all the food and medical supplies were destroyed when the business and warehouse districts burned. Shelter was an urgent need. Although several thousand people moved to nearby Portland or simply left the Saint John area altogether, a considerable number of city residents had nowhere to go. The Victoria Skating Rink on City Road served as a temporary shelter for several days. Tents were erected on the Barrack Green and shanties were rapidly erected on King Square and Queen Square as homes for people and businesses.

Saint John's fire made headlines worldwide and soon assistance began to pour in. Cities from San Francisco to Glasgow donated funds and in total over $225,000 was received. Chicago, which suffered a similiar fire a few years previously and recalling Saint John's generosity in its time of need, sent $10,000. The federal government's contribution was $20,000. Hundreds of businesses, churches and individuals sent financial aid and offers of help. The supplies and foodstuffs received were stored and distributed from the Victoria Skating Rink. Initially the distribution process was haphazard until a Relief and Aid Society was organized to ensure those in the most dire need received assistance promptly. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows and other fraternal societies organized relief efforts to aid fire victims. The Order raised $4000 itself by canvassing membership throughout Canada and the United States despite the organization's headquarters in Saint John being burned out. Saint John's fire made headlines worldwide and soon assistance began to pour in. Cities from San Francisco to Glasgow donated funds and in total over $225,000 was received. Chicago, which suffered a similiar fire a few years previously and recalling Saint John's generosity in its time of need, sent $10,000. The federal government's contribution was $20,000. Hundreds of businesses, churches and individuals sent financial aid and offers of help. The supplies and foodstuffs received were stored and distributed from the Victoria Skating Rink. Initially the distribution process was haphazard until a Relief and Aid Society was organized to ensure those in the most dire need received assistance promptly. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows and other fraternal societies organized relief efforts to aid fire victims. The Order raised $4000 itself by canvassing membership throughout Canada and the United States despite the organization's headquarters in Saint John being burned out.

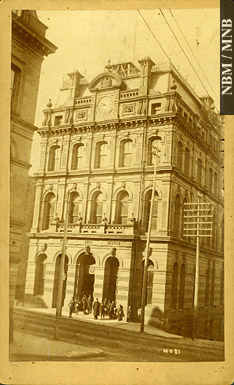

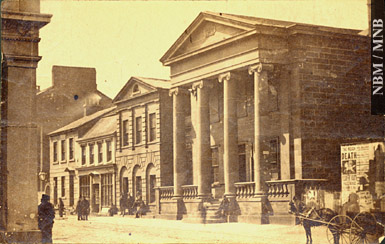

City residents, exhibiting a strong sense of community spirit and pride turned immediately to restoring the city. Nearly $7,000,000 in insurance payments and an estimated $1,500,000 in mortgage loans were available to finance reconstruction and additional money was raised. The federal government built the new Post Office and the Custom House on Prince William Street. The civic and provincial governments were responsible for the construction of City Hall and the police and fire departments. Merchants ordered plans for new premises drawn up even before the smoke had ceased. Workmen began clearing rubble immediately so that within four weeks little evidence remained of the ruins. In most instances public buildings constructed after the fire were made of brick and stone and were subject to new and more stringent fire regulations. Many residential structures, though, continued to be made of wood. Within a year of the fire, 1300 buildings were constructed and with hundreds more rebuilt in the next decade as funds became available and the city renewed. City residents, exhibiting a strong sense of community spirit and pride turned immediately to restoring the city. Nearly $7,000,000 in insurance payments and an estimated $1,500,000 in mortgage loans were available to finance reconstruction and additional money was raised. The federal government built the new Post Office and the Custom House on Prince William Street. The civic and provincial governments were responsible for the construction of City Hall and the police and fire departments. Merchants ordered plans for new premises drawn up even before the smoke had ceased. Workmen began clearing rubble immediately so that within four weeks little evidence remained of the ruins. In most instances public buildings constructed after the fire were made of brick and stone and were subject to new and more stringent fire regulations. Many residential structures, though, continued to be made of wood. Within a year of the fire, 1300 buildings were constructed and with hundreds more rebuilt in the next decade as funds became available and the city renewed.

In the fire, no fewer than five photography studios were destroyed. In some cases, years of negatives and proof ledgers along with business papers disappeared. Fortunately though, images of Saint John from the late 1850s to June 1877 had been printed and sold so that a record of the urban landscape was preserved. To date, no photographic images of the fire itself or activities of the citizens in their plight have come to light. The few saved equipment, or whose studio had not been affected, managed to document the devastation. Within a year some photographers reestablished themselves and the photographic recording of the city's new growth was ensured. In the fire, no fewer than five photography studios were destroyed. In some cases, years of negatives and proof ledgers along with business papers disappeared. Fortunately though, images of Saint John from the late 1850s to June 1877 had been printed and sold so that a record of the urban landscape was preserved. To date, no photographic images of the fire itself or activities of the citizens in their plight have come to light. The few saved equipment, or whose studio had not been affected, managed to document the devastation. Within a year some photographers reestablished themselves and the photographic recording of the city's new growth was ensured.

|